Winter work plans, plus the history and future of geo-thermal, especially in Cornwall

Rain is hammering down on the roof and windows, so loud that the radio newsreader’s voice is almost drowned out. I know we need the rain for our rivers but must confess that I really struggle with this time of year! Clocks going back, our outdoor displays being blown to pieces by gales and – as a result – a big, expensive list of winter work to do.

One thing I have been dreading is the day when we must repair and reinforce the frame for my biggest solar array. I have chosen winter for this renovation, because there is not that much sun … not so much money to lose!

The wood you see has been in place for 7 years with some parts clearly now rotting. It was a big relief to get the panels safely indoors this morning and to find the frame is not that bad. I won’t explain about the tyres yet, but you will see them in the final re-design.

Geothermal Energy

What does it mean?

- Geo, relating to earth/soil & rocks.

- Thermal, relating to heat.

- Energy, power derived from using physical or chemical resources, especially to provide light and heat or to work machines.

Knowing that I was due to visit the geo-thermal developments at Eden Project, I decided a bit of background research wouldn’t go amiss. So, I began with the two types of geothermal – very simply, there is wet and dry … Hot Wet Rocks (HWR) or Hot Dry Rocks (HDR).

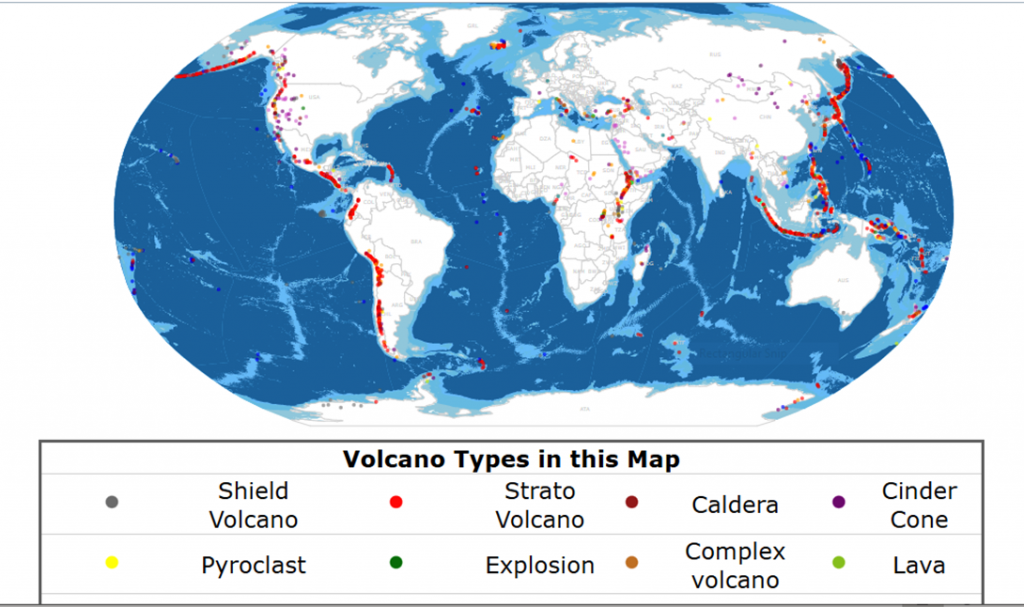

HWR have been known by indigenous peoples in North America and used as a heat and washing water source for over 10,000 years. The best/easiest sources occur in volcanic areas, because the hot magma (you may be more familiar with the word lava, but both mean high-temperature, melting rocks) can be close to the surface, with steam or hot water spouting out of the ground. If you happen to have travelled to any of the areas, shown red on a map below, you may have seen one of these dramatic hot springs, such as the Old Faithful Geyser in Yellowstone Park, so named because it erupts every 65 minutes, as regular as clockwork, or the Strokkur in Iceland.

This extract is from the guide to Iceland – https://guidetoiceland.is/travel-iceland/drive/strokkur and is accompanied by a lovely photo kindly supplied by a friend from Berkshire.

Active geysers like Strokkur are rare around the world, due to the fact that many conditions must be met for them to form. They are thus only found in certain parts of highly geothermal areas.

The first condition that is necessary is an intense heat source; magma must be close enough to the surface of the earth for the rocks to be hot enough to boil water. Considering that Iceland is located on top of the rift valley between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, this condition is met throughout most of the country.

Secondly, you will need a source of flowing underground water. In the case of Strokkur, this comes from the second largest glacier in the country, Langjökull. Melt-water from the glacier sinks into the surrounding porous lava rock, and travels underground in all directions.

Evidence of this flowing water can be found in Thingvellir National Park, where there are many freshwater springs flowing straight from the earth.

Finally, you need a complex plumbing system that allows a geyser to erupt, rather than just emitting steam from a vent in the ground (called a fumarole). Above the intense heat source, there must be space for the flowing water to gather like a reservoir. From this basin, there must be a vent to the surface. This vent must be lined with silica so that the boiling, rising water cannot escape before the eruption.

There is a great deal more to learn about Iceland. It is now almost 100% self-sufficient, using only sustainable energy sources, rather than the fossil fuels that were imported up to the 1970s. It also has a very advanced system of carbon capture into rocks; more on this from UNESCO (as the island has a total of 3 World Heritage Sites!) https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/carbon-capture-and-storage-plant-becomes-operational-iceland

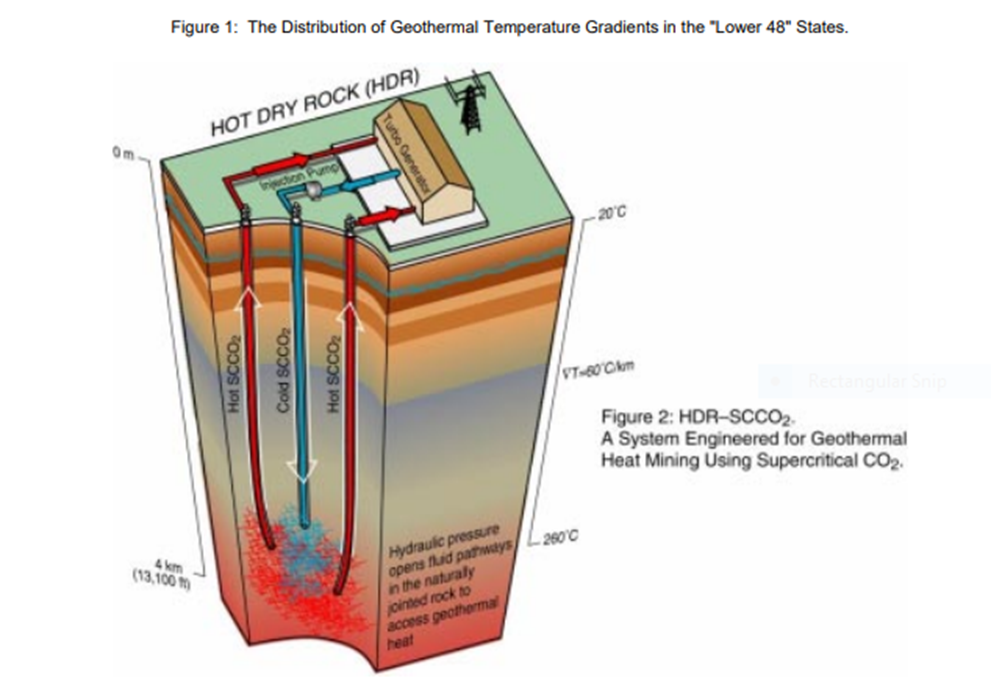

Hot Dry Rocks

This is the kind of geo-thermal at Eden Project and a couple of other locations in Cornwall. In most cases, and certainly in this county, the idea has been to introduce ordinary water, with a few additives (biocide and an anti-corrosive) into the hot dry rocks at depths of around 5 km, using a closed loop system … water goes down cold, and comes up very hot. The hot water can be used for underground heating systems or sometimes can drive turbines that make electricity.

The HDR type of system, unlike fracking, does not involve blasting. Instead, the water tubes are introduced into natural rock fractures, using bore hole drills. For completeness, let me also mention the experimental use of another liquid – Supercritical CO2. A research paper reports ‘the advantages of using SCCO2 in a power-producing man-made HDR geothermal system appear to be considerable.’ PS I have really only included this, because I like their diagram!

The People

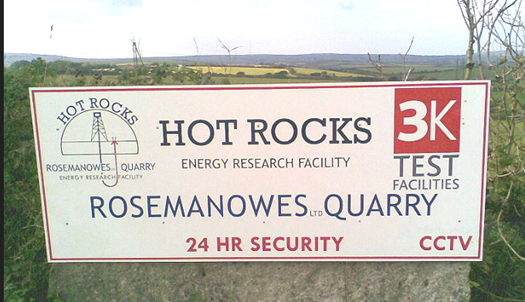

A week ago it was so interesting to sit back and listen to Augusta Grand, the C.E.O. of Eden Geothermal Ltd. We both agreed from the outset that the policy of Eden, that has led to so many women being appointed to leading roles like hers, deserves to be flagged up and celebrated. Supported by one of Cornwall’s most experienced geo-thermal experts, Tony Bennett, Gus is able to focus on the bigger picture. Her own academic background was in Tropical Horticulture but – from her first appointment at Eden in 2001 to work with soils and early sustainability projects – she had the burning ambition to see Eden operate off-grid. After a very tricky initial attempt to install a massive wind turbine (NIMBYs picketed in opposition), Gus was made aware of HDR when some engineers made contact. They were from EGS Energy and had worked on a small test operation at a quarry near Falmouth, called Rosemanowes in the 1980s. Today the quarry owners, Avalon Sciences.com, have totally upgraded the premises, to offer state-of-the art testing for geothermal, with a particular focus on seismic activity. Their 9 inch wide bore holes enable analysis of performance, in the best rocks of the UK. Speaking for the company, Will told me ‘We used to travel to Texas until we realised that west country granite has what we call the best GOOD Q or quality, for transmitting signals through the ground. We often start making signals with a massive hydraulic plate, then use our specialist equipment to record how it diffuses.’

Based on those initial consultations with Rosemanowes, the first idea for Eden Geothermal, announced in 2009, was to lease the land to EGS Energy so they could undertake the development and sell power to the grid. Very soon, in 2010, those plans were scuppered, by the financial crash. The Eden team had to re-set, acknowledging that a different approach and public funding would be needed. At this point the support of Cornwall Council was critical, as ideas were coming together for a bid to suitable EU funding streams. The estimated project cost in applications submitted in 2016 was GBP 16.8 million but a final figure for the first well (with possibly a 2nd to follow) is now expected to be GBP 17.3 million (around USD 23 million). The rise has been due to various events, Brexit being a predictable one but all the others being entirely unexpected e.g. the pandemic, closure of the Suez Canal and the Ukraine War.

Money came in and work began in 2019. It was always anticipated that some headaches would arise, possibly due to very hard rock (in nearby Luxulyan Valley the historic description was of ‘adamantine granite’). But other natural challenges came up, with the discovery of dormice (18 months taken to re-locate them safely!) and a very rare and strange chemical/biological reaction between some drilling fluids made of xanthan gum, baryte and bentonite clay and an unknown bacteria, probably sulphur-based. Mixed together these substances started bubbling away, eating up sugars and creating CO2. Very unexpected and not at all desirable, is how I would sum this up!

Once begun, drilling was continuous. Two x 12 hour shifts a day were maintained, even through the pandemic, by a team of about 45 people of which the major hands-on drilling experts were from the Czech Republic.

During 2022 big strides forward have been happening, mainly behind the scenes. 4 different heat systems had to be installed and be capable of combination into the Heat Main, ready to receive vacuum insulated tubing with the hot water and then utilise it in a kind of cascade – from the hottest in the tropical biome to the lesser heat of greenhouses, offices, shop and café. Some of the journey can be gravity fed, but otherwise there is a need for electrical pumping.

January 2023 is the hoped-for date of full operational testing, with time to iron out any issues that arise well before the busy visitor season. There will be no resting on laurels however, as Gus told me that geothermal options are becoming ever more vital in the council’s aim for Cornwall to be carbon neutral by 2030, with quite a number of future sites under consideration. More widely, geothermal is very much the new go-to solution, for the planet’s sustainable future.

Winter. Some activities that will run despite the rain!

Later today, Friday 4th, we will be part of an online discussion and planning session of 3 hours, dedicated to the restoration of our Luxulyan leat system, under the banner of Luxulyan Valley Partnership. There will be plenty of experts, but I am very proud that our Meadow Barns guru, David Skelhorn, will be contributing a major set of proposals.

Related to this, David and I will also be leading the ‘Big Green Adventure Day, to walk the entire leat system, on TUESDAY 15TH NOVEMBER. Please see the 2 flyer pages below for full details and use Messenger, email or text your details to be included on the list. cjs@themeadowbarns.co.uk or 07967 653346.

There will be further winter activities for your interest and engagement next time. But for now, take care at those firework events and enjoy your weekend. Caroline